With Love

short story

They divorced, with love, on a Tuesday.

The papers sat elephantine on the kitchen counter for one rainy week as they promised one another they would not sign until a bright day came and lifted a measure of heaviness. On the penultimate Monday the rain sputtered to a stop but the cloud cover hung low and insistent, quietly smothering. Jon in the yard tossing wet sticks for the dog. Rory in the attic looming over cluttered boxes, not touching, only looking. They slept in the same room.

On Tuesday, they woke to dripping sun and birdsong. The papers were signed over coffee using the same pen. A marriage dissolved in the wake of a flood. With love on a Tuesday.

What will you do for hump day, Jon had asked him, coffee-breathed. Who will you hump.

What? Rory said. Like that was something we did? We haven’t had sex in two years.

I know. Tracing pale circles around his bare ring finger. I need to joke. It’s the only way through.

I know.

I wish I wanted to have divorce sex.

I know.

But I just don’t.

Jon’s sister came in a rented van to move him out. A day grown hot but too pleasurable to rebuke. The van filled up and the house half-emptied. The dog sniffed around all the vanishing fixtures and searched for answers in the upheaved dust motes. It was late when they finished, no sense setting off in the dark, so they ordered a large pizza from the place they knew well and though the couch was Rory’s, the couch would remain, they sat on the floor lifting sagging slices to their tongues and spooning greasy cheese down the hatch.

The TV went to Jon, sat idle in the van, so Rory laid a record on the player: Feist’s The Reminder–never one for subtlety. We don’t need to say goodbye.

And they three listened with eyes closed and throats humming, Viv singing, following the record’s rhythms from regret to jubilance to heart-open despair, and when those quiet moments between songs grew swollen with the burden of all the days to come, Rory would take Jon’s hand and return them to the current day, the only one.

Wine, Viv said after some time and though someone likely should have argued against this, none could push past it, this childish instinct to wet difficult moments so that they might pass more easily.

The wine opener laid solemn in a mislabeled box in the van; Rory would have to get another for himself, one that did not know his habits. He scissored the cork the way they did in college, breaking it to bits in the dark red. Laughing about it. They raised their glasses to something unnamable and regretted it.

We can’t be friends anymore, Viv said to Rory, chin in palm.

No, he confirmed. We cannot.

I wish we were like that, Jon said. I wish we were people who could stay friends after.

You are always my friends, Rory said. We just can’t be friends.

He flipped the record. There’s a limit to your love: Which bends and warps and you watched all the warping and bending so you recognize it all the way through, changes too subtle for the eye to discern. It’s the unbent thing which is lost to you, which you no longer know and hadn’t known was being lost.

That’s what Rory had said to their wide-eyed marriage counselor in her vintage armchair but she hadn’t understood. She asked about their communication. Time’s erosion cannot be conveyed in words. In the parking lot outside her office, Jon smiled beneath fluorescent light and they both knew and the cracks in the pavement knew and the tiny kamikaze bugs knew. The nagging sense that even their eighteen year old selves had known: Jon’s first smile the echo of his last.

The dog, too anxious to enjoy his pizza scraps, couldn’t help his own sadness. He could tell with his doggy eyes the growing fracture beneath his doggy paws. He knew someone was leaving but not who. He paced in circles, tongue wagging its pleas. Staring out the porch door into the dark, ears perked, as if whoever was leaving might already be returning. Maybe it would work like that for him.

It was Viv who cried in the end, at the bottom of the bottle, which was funny and then sad. She said, weepy, I miss it all, and they agreed. Jon carried her to their bed and the newly-unweds convened in the living room. Heads go on shoulders, they know each other well. Swaying gently to a future tough memory.

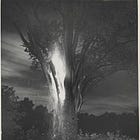

I’m thinking about the tree falling in the backyard, Jon said.

Hm, went Rory’s tight chest. We shouldn’t reminisce.

I’m just wondering if it meant something is all.

If it meant something about us. Like a message.

Something like that.

Well, of course I think it meant something. I can make meaning out of coffee rinds.

But you’re a psychopath.

I am.

It meant something different to both of us, I can tell. But we never said it out loud. Is that the problem?

There’s no problem, Jon. Something came to pass and now it’s long behind us. Your meaning is in the forward walk.

Jon sniffled. I won’t be able to look back.

Not for a while, no.

They slept on the same couch in the same room with the absence of some homely ambience. The dog huffed and paced and leered at hollow shadows.

The sun rose in battle with the clouds to make a day worth inhabiting. The light won out and chased misery off to some future storm. Tiny bugs skittered all across the lawn. With too much to say and no use in adding any of it to the humid-thick air, there were quiet hugs exchanged in the drive, doors closing too loud for the early hour, tapping the van’s bumper like a nice ass. Engine chugging to life. The dog sitting, standing, sitting, crying. Two realities running separate now as rivers diverge. The van pulled out slow then rounded the bend quick and morning settled in all the same, but awfully different.

In the backyard, Rory toed the earth where that ancient tree had been storm-felled those three years ago and the stump dislodged from its home, then covered over.

He sprawled out in the grass there which was richer than all the other grass for what had died beneath the dirt. A blemish which refused to be removed entirely. The earth moved, metaphorically, beneath the dull blades of his shoulders. All of it is there, of course. Yes, the folded laundry, yes the tomatoes full in the garden, yes, the dog as playful drooling pup, yes, rain on the windows and kissing and avoiding and labored breathing and subtle reaching and each rising of the sun and every day come and gone will never really go. It is then and now and always. Lifeforms shifting beneath the crust of the planet; a thousand happinesses, a thousand helpless quibbles, immeasurable moments of neutral mundanity. A history which cannot be changed but is always making changes.

The dog licked at him and feigned play and then settled at Rory’s side where the two of them soaked in the hard-earned sunshine. When the big orb tilted at the right angle, spitting hard sepia rays through the lids of his eyes it felt like the future coming in second by second only to become the present. This one, forever arriving, so different than all the others. A missing thing that would continue to be missed even once the absence settled.

Rory palmed the soft, dewy grass and wondered could a tree grow there again—and how long would it take.

james worth wednesday is tender and heartbreaking and somehow the dog is the character I will take with me. how did you do that

Match of prose style, here quite stark and simple, there quite rhapsodic and lyrical, with the ebbing and flowing of the intimate and personal to the more, er, transcendental, is masterfully done.

I'll have more to say in due course, I reckon. Feel a lengthier appreciation incoming...